The Extremely Remarkable Story of Hasan Agha and His Brother Anton Chelebi

Purpose and Context

The project “A Global-Microhistorical Study on the 17th-Century Ottoman-Mediterranean World: Customs Officer Hasan Agha and His Brother, Gonfaloniere of Livorno, Anton Bogos Chelebi”, under the direction Dr. Mehmet Kuru, was awarded with support in 2021 by the TÜBITAK 1001 (The Scientific and Technological Research Projects Funding) program. The project aims to construct a global history narrative by focusing on two brothers who were important economic and political actors of the Ottoman and Mediterranean world in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Hasan Agha and his brother Anton(io) Bogos Chelebi were not only bureaucrats, but also wealthy merchants with extensive commercial networks. The story of these brothers presents a unique research topic that can provide us with new insights in the seventeenth-century Mediterranean/ Ottoman world from economic, political and cultural perspectives. While focusing on these two brothers, the themes that are explored are placed in a wider context, by taking into account the economic and political transformations witnessed in the Ottoman Empire and Mediterranean in the seventeenth century. In this manner this micro-scale case study is evaluated within a global framework.

The two brothers’ commercial connections from London to Isfahan (New Julfa) and their bureaucratic positions as customs officer and gonfaloniere are discussed on economic-political grounds. The social and spatial mobility of the brothers who were born as children to an Armenian father living in the Ottoman countryside and reached the highest bureaucratic positions in the Ottoman Empire and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, is analyzed. The religious conversion of the brothers, from Orthodox Christianity to Islam for one and from Orthodox Christianity to Catholicism for the other, will also provide us with the opportunity to trace contemporary dynamic cultural identities.

This multi-layered structure woven around Hasan Agha and Anton Chelebi is examined in detail with the help of digital humanities tools. With the help of databases, maps and graphics, new questions are asked to the historical narrative and analysis possibilities are expanded.

One of the brothers, who was born as the children of an Orthodox Ottoman Armenian from Bursa at the beginning of the seventeenth century, converted to Islam, took the name Hasan, and rose up to Istanbul Customs Officer by rising within the Ottoman bureaucracy. Customs Officer Hasan Ağa was among the statesmen killed during the Çınar Incident in 1656.

His brother Anton, who worked as a surety in İzmir and Bursa, fled to Livorno after the Çınar Incident, became a Catholic here, and was elected as a gonfaloniere after a while and presided over the city governing council.

Who are Hasan Agha and Anton Chelebi?

The two brothers were born as children of An Orthodox Christian Armenian subject from Bursa at the beginning of the seventeenth century. One of the brothers converted to Islam and took on the name of Hasan. Then, he climbed the echelons of the Ottoman bureaucratic system and achieved the post of Istanbul Customs Officer. Hasan Agha, now, was among the victims of the so-called Çınar incident of 1656.

His brother Anton, on the other hand, occupied the posts of customs official in Izmir and Bursa. After the Çınar incident, he escaped to Livorno, converted to Catholicism there and was as gonfalonier [standard-bearer]elected as the head of the administrative city council.

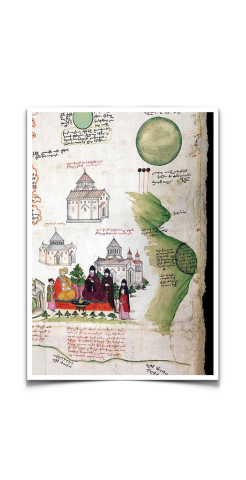

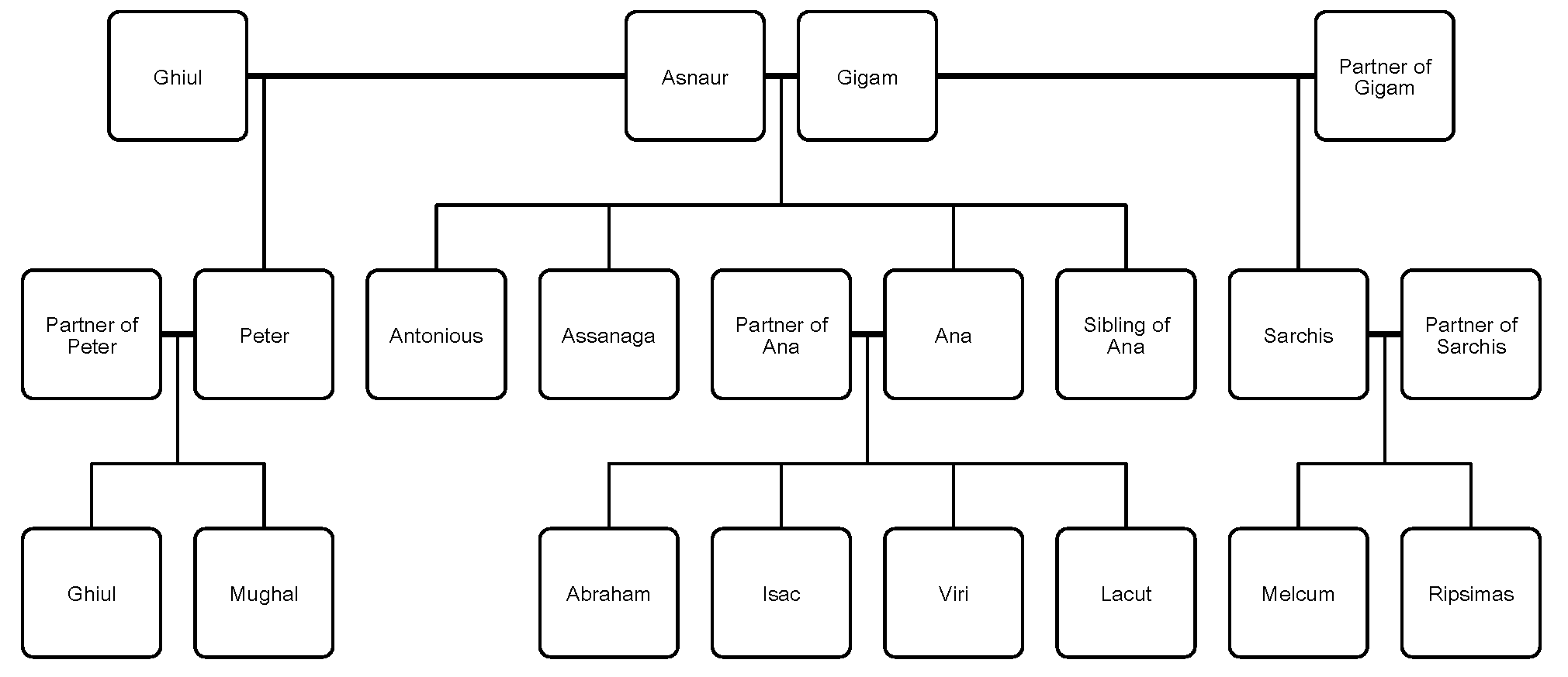

The family tree of Anton Bogos (Antonius Bogos) and Hasan Ağa (Assanaga) according to the inheritance proceedings dated 10 August 1678.

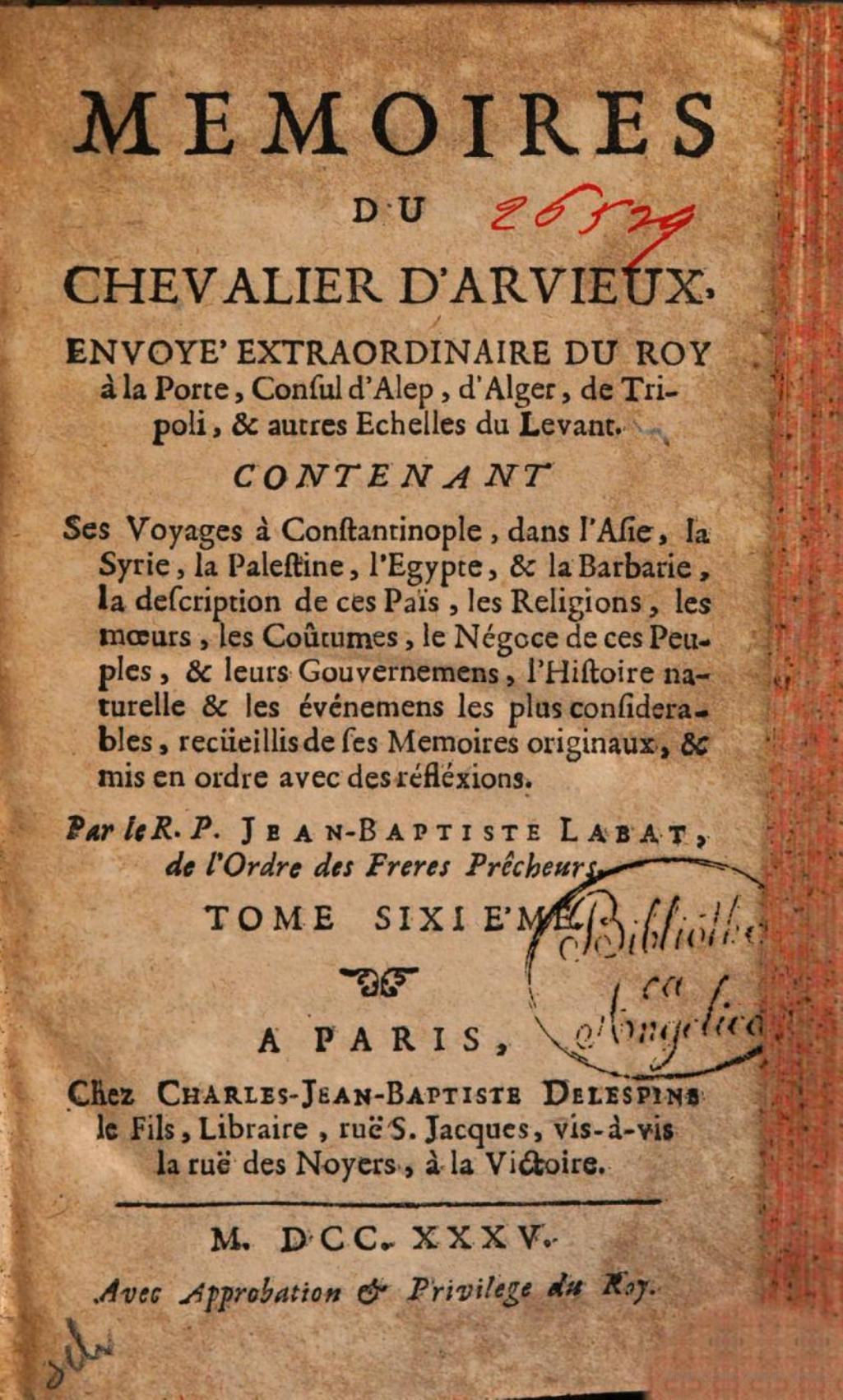

Anton Chelebi étoit Arménien de Nation, il étoit âgé de quarante-six ans quand je l'ai connu, c'étoit un homme bienfait, un peu brun, d'une belle physionomie, plein d'esprit, & Chrétien. Il savait en perfection les Langues Turque , Grecque , Espagnole , Italienne, Angloise, Persane & Arménienne, qui étoit sa Langue naturelle. Il étoit Cuisinier chez un Marchand Anglois, dans le temps que son frère, jeune homme très-beau & très-bienfait, plût au grand douanier de Constantinople, qui le prit à son service, l'engagea à se faire Turc, & lui donna le nom de Hassan Aga. Il demeura au service du grand douanier, jusqu'à ce que le Grand Seigneur fit mourir son Maître. Comme il avoit le secret de ses affaires, sa veuve ne fit point de difficulté de l'épouser, de sorte qu'il se vit tout d'un coup fort riche.

Les Ministres du Grand Seigneur qui connaissaient son esprit & son expérience, le proposèrent au Grand Seigneur pour remplir le poste de son Maître, & il eut la Charge aussi-bien que sa veuve. Dès qu'il fut en charge, il songea à son frère Anton Chelebi , & il l’employa dans la douane de Smirne et dans d'autres Commissions, où en peu de temps il fit des gains si prodigieux, qu'il avoit des Palais dans les Villes Imperiales, grand nombre de Vaisseaux sur mer, de grandes sommes dans toutes les Banques de la Chrétienté, & un commerce immense dans l'Europe & dans l'Asie, & par tout. Il se faisait honneur de son bien. Il n’alloit jamais à la campagne qu'avec un train qui faisait honte à ceux des Gouverneurs de Province.

Ses grands biens ne manquèrent pas de lui attirer bien des envieux & des ennemis ; mais personne n'osait se déclarer, à cause du grand crédit où étoit son frère à la Cour, que l'on y estimait beaucoup, à cause de sa libéralité , de son équité, de sa politesse & de la charité , qui le portoit non-seulement à assister les pauvres qui avoient recours à lui , mais encore à faire bâtir des Hôpitaux & des Caravansérails, & à les fonder,& même des Forteresses.

Ses grands biens ne manquèrent pas de lui attirer bien des envieux & des ennemis ; mais personne n'osait se déclarer, à cause du grand crédit où étoit son frère à la Cour, que l'on y estimait beaucoup, à cause de sa libéralité , de son équité, de sa politesse & de la charité , qui le portoit non-seulement à assister les pauvres qui avoient recours à lui , mais encore à faire bâtir des Hôpitaux & des Caravansérails, & à les fonder,& même des Forteresses.

Mais comme les gens d cette considération ne durent pas long-terms, & que leur fortune & leurs biens sont ordinairement des motifs pour les perdre ; on lui rendit de mauvais offices auprès du Grand Visir, que l’avarice [ 95 ] & l’envie d’avoir les grands biens du Douannier portaient assez à lui faire perdre la vie. L’ordre de l'étrangler fut expédié deux fois, & deux fois Hassan Aga eut le bonheur de conjurer la tempête & de sauver sa vie à force d’argent. Mais il ne put échapper à un troisième ordre. On le surprit chez-lui, on l'étrangle promptement, & ses biens furent confisqués au profit du Grand Seigneur.

Sources and Methods

The research of the history of Hasan Agha and Anton Chelebi that exceeds the borders of the Ottoman Empire, is conducted in the archives of five different countries. An important contribution of this study in terms of method is to associate the data obtained from these archives with one another and to make an analysis that will provide historical knowledge.

Ottoman Archives: There are many documents and records available on Hasan Agha and Anton Chelebi in different classifications in the Presidency State Archives (Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri), Court Records (Şer'iyye Sicilleri), and the Foundation Records Archive of the General Directorate of Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü Vakıf Kayıtları Arşivi).

French Archives: Research is done at the Departmental Archives (Archives Départementales) at Bouches-du-Rhône in Marseille to examine Anton Chelebi's commercial relations with Marseille.

Italian Archives: Anton Chelebi, who lived in Livorno between 1656 and 1674, left many records in the archives of Livorno (Archivio di Stato Livorno), Florence (Archivio di Stato Firenze) and Venice (Archivio di Stato di Venezia).

Dutch Archives: Customs officer Hasan Agha and his brother Anton Chelebi had intense commercial and diplomatic relations with the Netherlands. Our ongoing work in the National Archives in The Hague and City Archives in Amsterdam focuses on these relationships.

UK Archives: The National Archives of the UK contain information about Hasan Agha and Anton Chelebi regarding their commercial operations. The frequent presence of the brothers Hasan and Anton in the documents of the English ambassadors and merchants of the Levant Company who served in the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century are important reasons to examine the UK archives more closely.

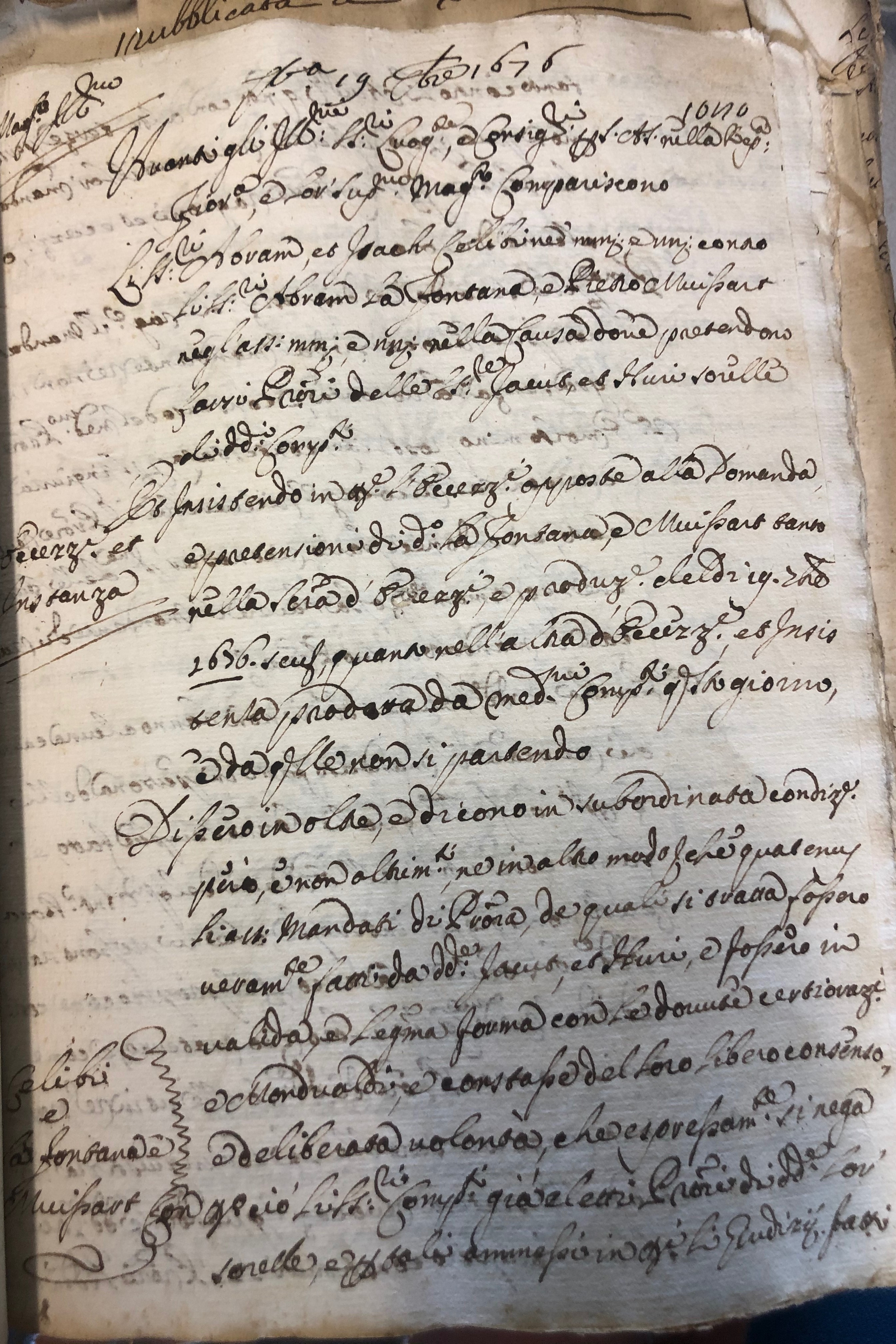

Presidency of Turkey, State Archives

Presidency of Turkey, State Archives

Archivio di Stato (Firenze)

Archivio di Stato (Firenze)

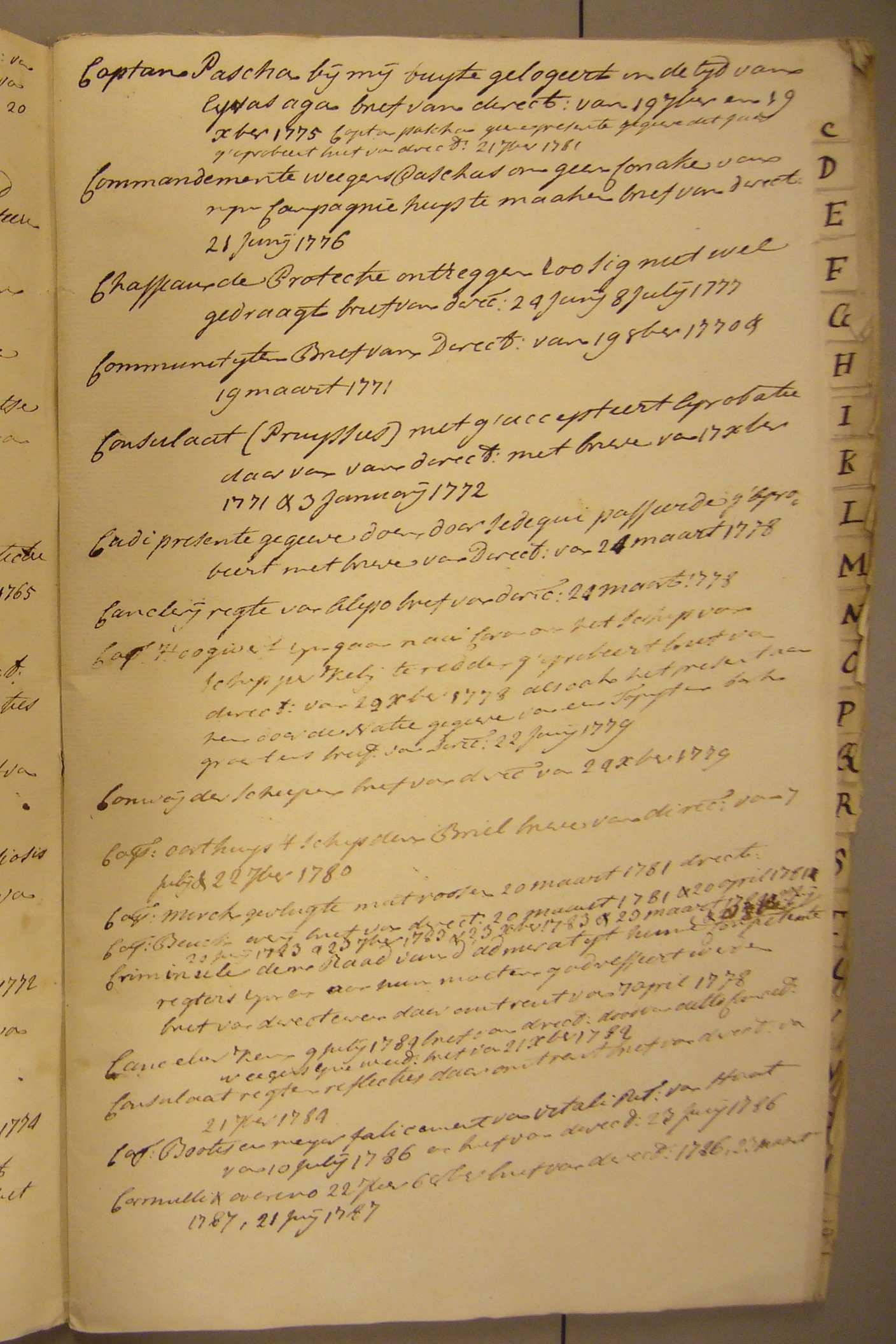

The Hauge, Nationaal Archief, 1.02.22 (Consultaat Smyrna)

The Hauge, Nationaal Archief, 1.02.22 (Consultaat Smyrna)

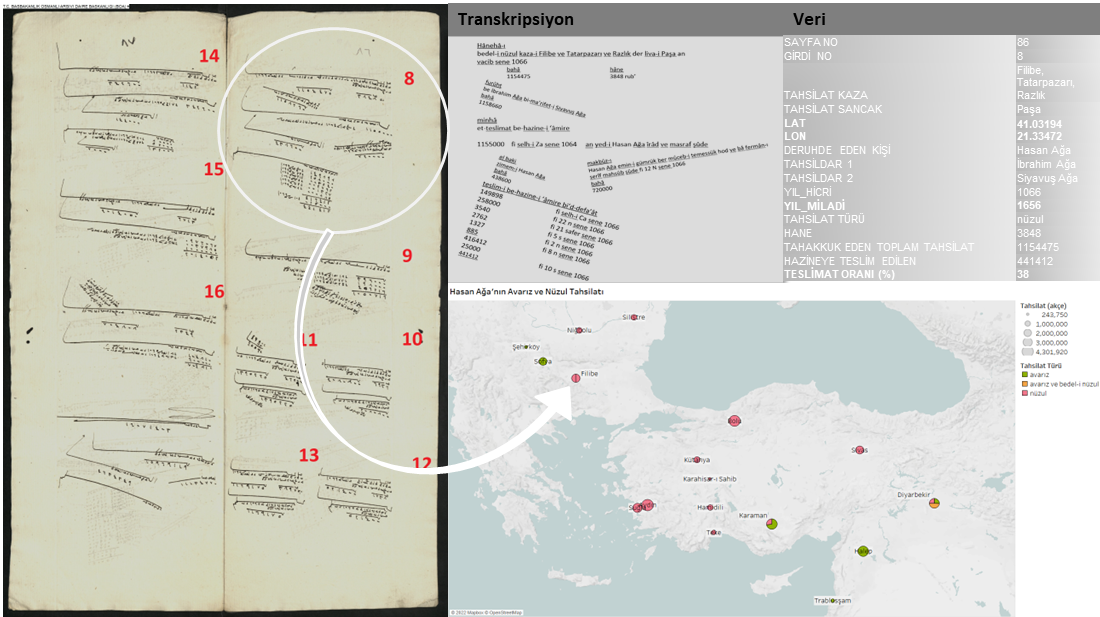

From Archive to Digital Data

The methods to be followed to access the digital data from archival documents are based on the tight ties that historians establish between the documents and digital humanities tools. In this example, the steps of transcribing the document, selecting the data to be used in the research, the cleaning and categorizing for placement in the data table, determining and coordinating the current equivalent of place names, and showing the quantitative and qualitative data in the document together on the map with the help of different signs (circle size and color code) can be seen. The map that was drawn is just one of the tools that helps the historian to explain and interpret the information that has been obtained from the archive.

Hasan Agha’s Financial and Administrative Power

The Rise and Fall of Hasan Agha

How did Hasan Agha rise to power in the Ottoman bureaucracy? When he came to Istanbul from Bursa, what relations did he establish within the agha/pasha household he was involved in? What were the extensions of the political network he was a part of after he became the Kitchen Executive and how did he gain power through this network? In this context, with whom did he enter into relations with the Palace? Which ruling factions did Istanbul belong to as Customs Officer? The fact that he was killed during the Çınar Incident (Vaka-i Vakvakiye), one of the most important political events of the seventeenth century, is an important ground for examining the power factions in which Hasan Agha was involved. Through this incident and Hasan Agha himself, it will be attempted to reveal the dynamics of the palace and Istanbul politics in the middle of the seventeenth century

A registry in the Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives with code MAD.d.12585, at first glance, reflects a language similar to the other avarız (property) and nüzul (feeding military forces) tax records in the catalog:

"Sefere memur askerler için alınan nüzül zahirelerinin memuriyet mahalline irsali müşkil görüldüğünden bunların en yakın Tuna iskelelerine sevki veya her bir avarız hanesi için ve haneleri olmayan reaya için tayin olunan bedelin ve mübaşiriyenin alınarak ziyade para aldırılmaması, her yer için tayin olunan avarız ve nüzül miktarı ile teslimatı ve 1060 senesinden 67 senesi gayesine kadar tahrir olunan avarız bakaya defterleri, sağ ve sol ve orta koldan tayin olunan bedel-i avarız ve nüzül defteri. Gümrük emini maktul Hasan Ağa'ya, maktul deli birader Ahmed Ağa'ya ve has odabaşı maktul Hasan Ağa'ya ve tersane emini maktul Salih Ağa'ya, Ohri Beyi Mehmed Paşa'ya avarız ve bedel-i nüzülden tahsil için mevkufattan verilen bekaya ve maliye defterleri. Kürekciyan bedelatı defteri ve bunların muhasebesi hakkındaki kayıtları ihtiva eden defterin içinde Yenice-i Karasu'yun bedel-i avarızına itiraz edenlere ait bir ilam ve bazı tahvilattan ordu hazinesine yapılan teslimata dair iki vesika mevcuttur."

(Registries concerning the following: since it was seen that the dispatch of the nüzül provisions taken for the officer soldiers on expedition to the civil service station was difficult, their dispatch to the nearest Danube piers or the rather not taking more money when the cost that is assigned for each avarız household and for the reaya without dwelling/ household and the mübaşir (bailiff) tax is taken; the amount and delivery of the avarız and nüzül amount that is assigned everywhere and registries of avarız tax arrears that are registered from the year 1060 until the year [10]67; and registry of avarız tax costs and nüzül taxes that are assigned from the right, left and middle subsections. Registries of absentees and revenues that were given from withheld money and property (mevkufat) for the collection from the avarız tax and the cost of nüzül tax to Ohri Bey Mehmet Pasha for the late Customs Officer Hasan Agha, the late deli birader Ahmed Agha and the late Master of the Robes (has odabaşı) Hasan Agha and the late Shipyard Officer Salih Agha. There are two documents regarding the delivery of some obligations to the army treasury and a verdict belonging to those who objected to the cost of avarız tax of Genisea, in the registry containing the Kurekciyan fee registry and its accounting records.)

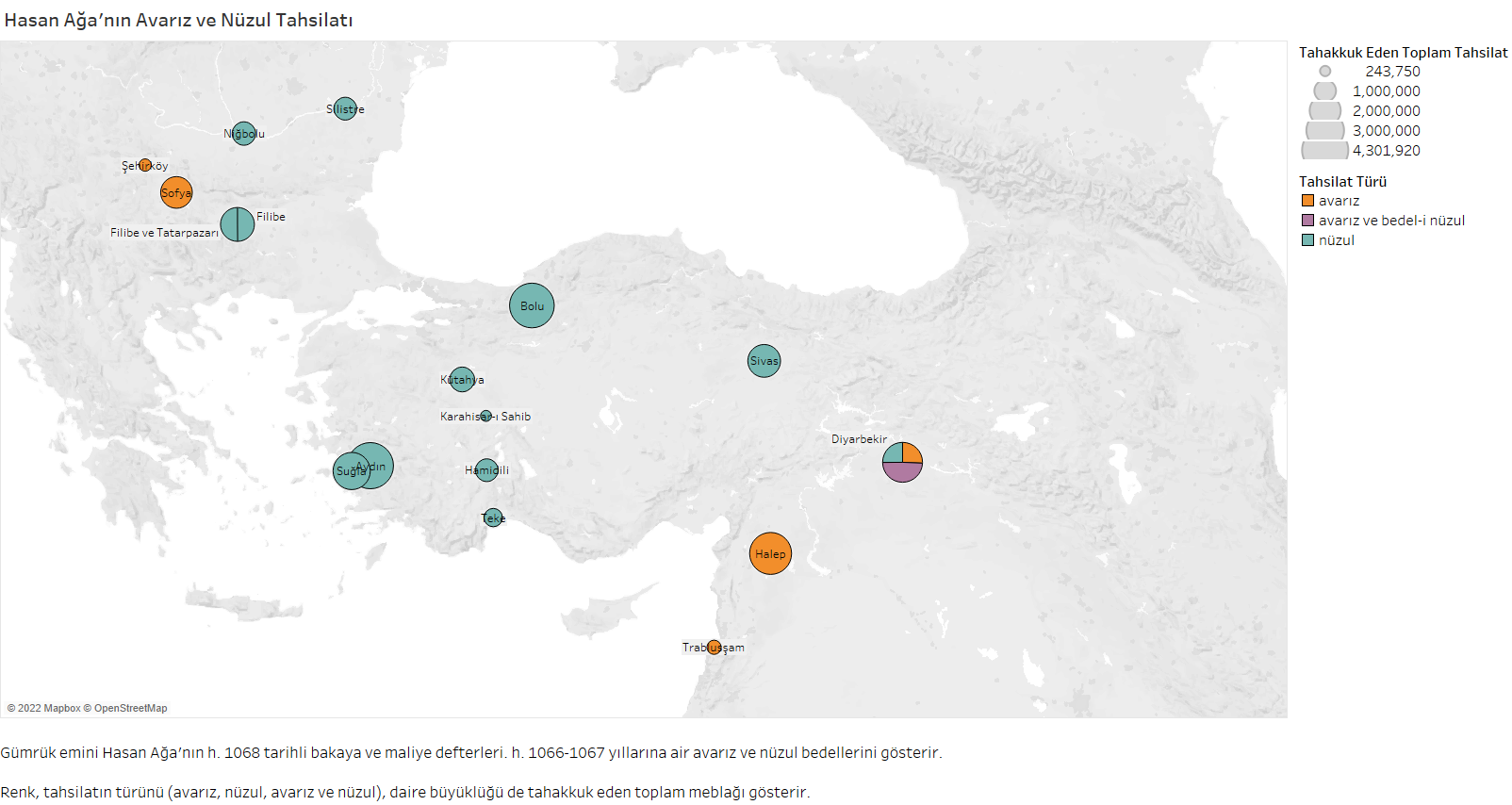

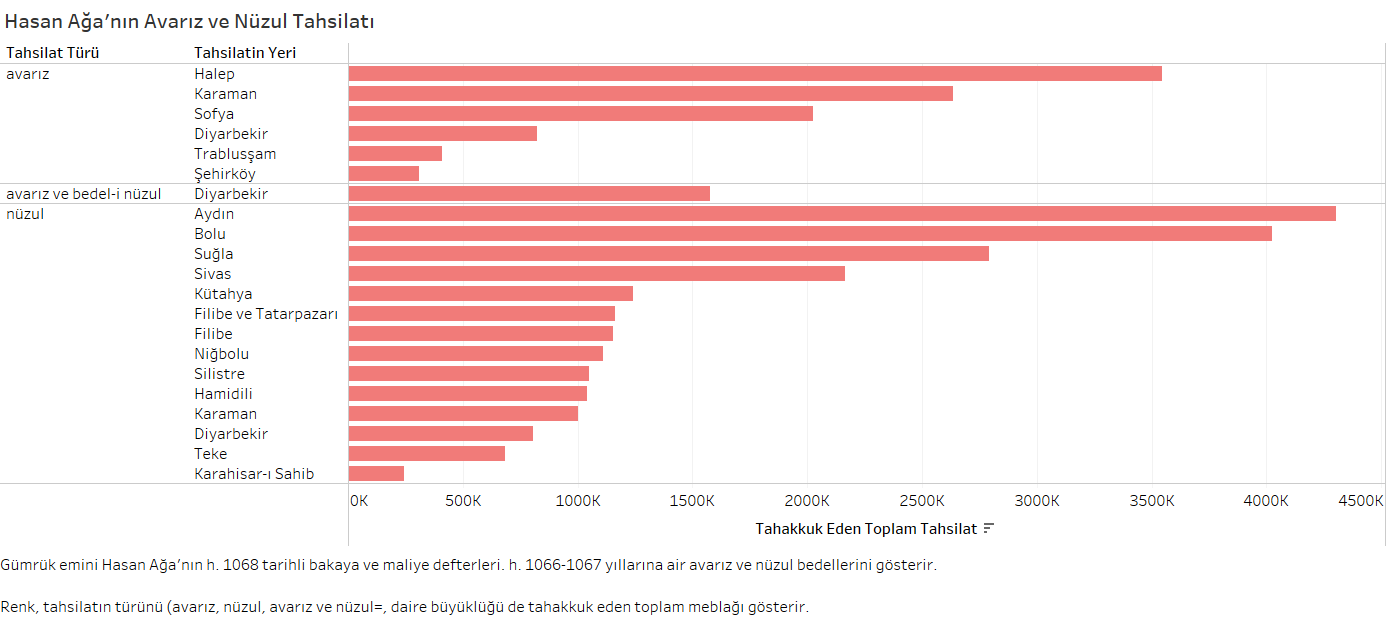

However, there is a common feature of these deceased mentioned in the registry summary. All of them are the aghas who were hanged together with Hasan Agha in the Çınar Incident. However, according to historical narratives, the rebels who participated in the Çınar Incident claim that they acquired unjust enrichment thanks to the tax obligations illegally collected by the palace aghas as the reason for their rebellion, perhaps in order to legitimize their rebellion. The relevant registry gains an exceptional importance when considered together with historical narratives. The entire registry, which is quite voluminous, is analyzed as part of the research within this project. Examining the section of the registry on Customs Officer Hasan Agha with the data visualization and mapping tool Tableau Desktop demonstrates the extent and depth of the network that Hasan Agha penetrated within the imperial bureaucracy.

Hasan Agha’s Provincial Network

What are the dimensions of the economy directed by customs officer Hasan Agha? The aim is to uncover the size of the economy that Hasan Agha ruled by revealing the customs he controlled, the other taxes he was assigned to collect and the salaries he was responsible for distributing over all these taxes.

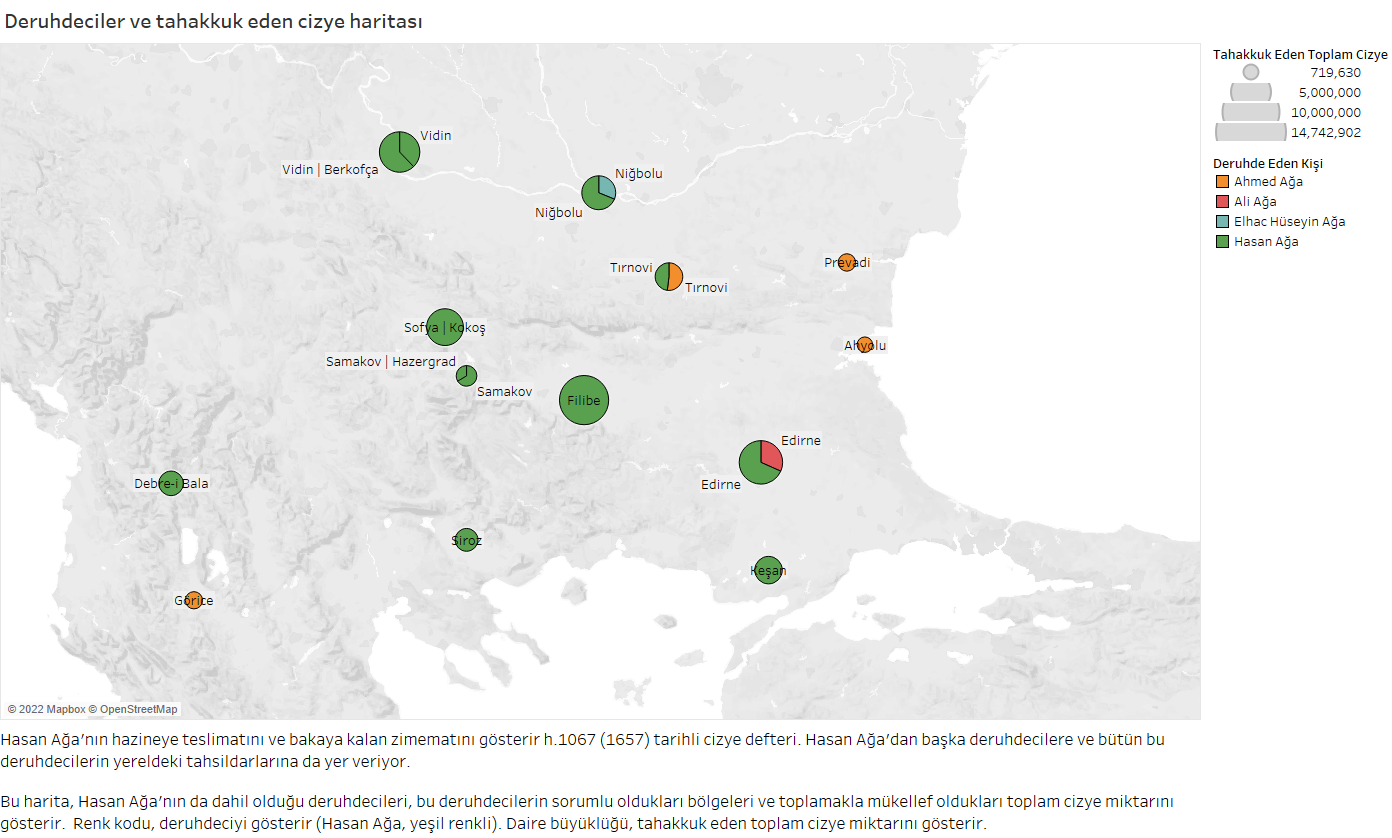

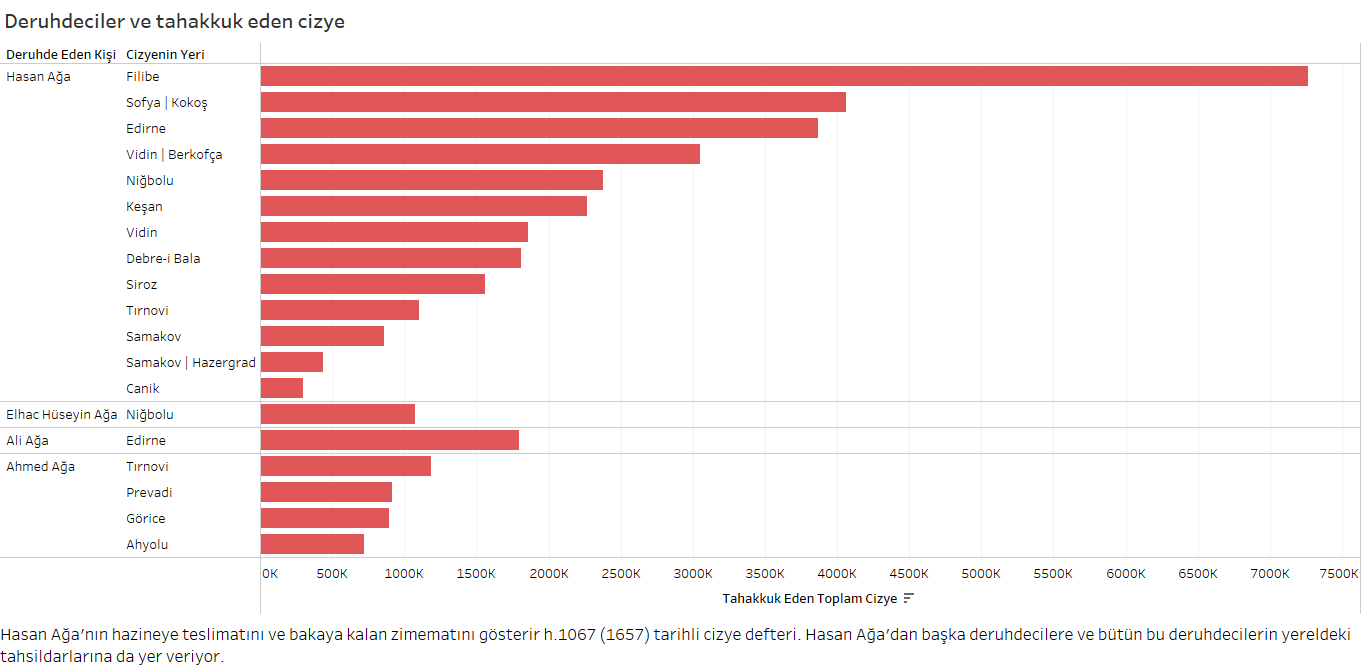

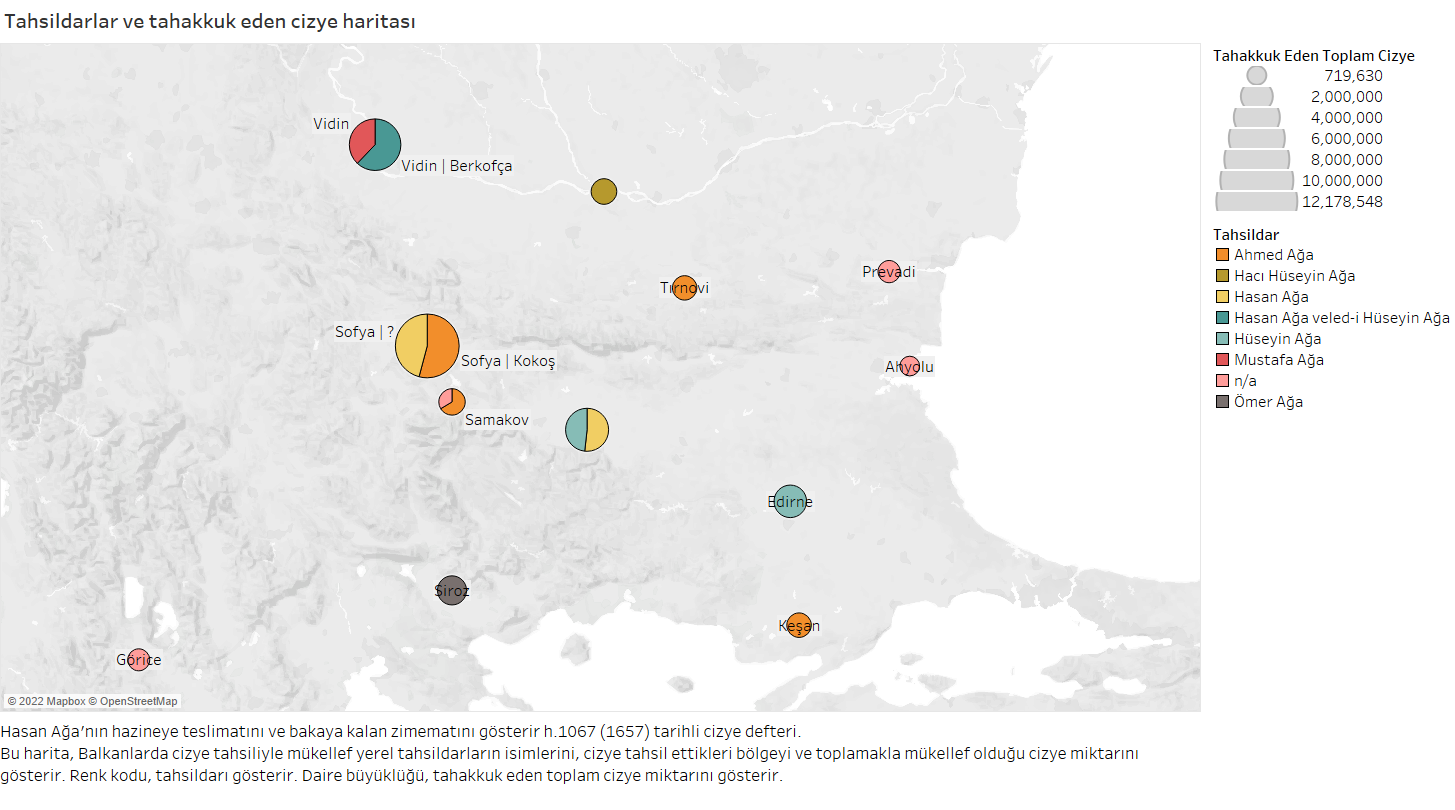

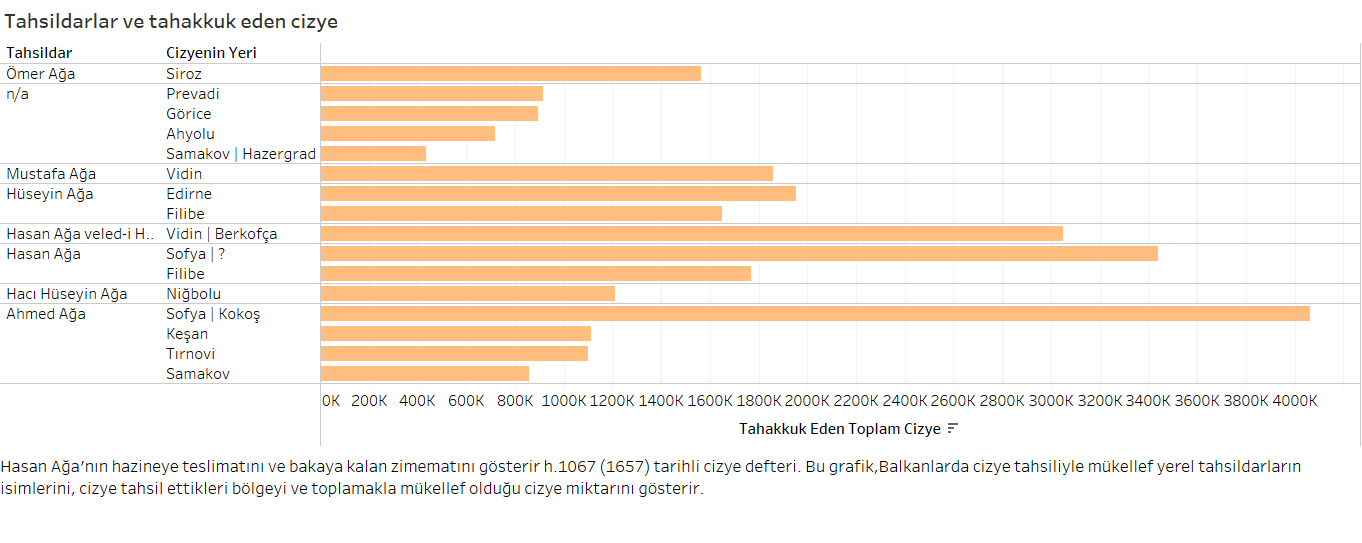

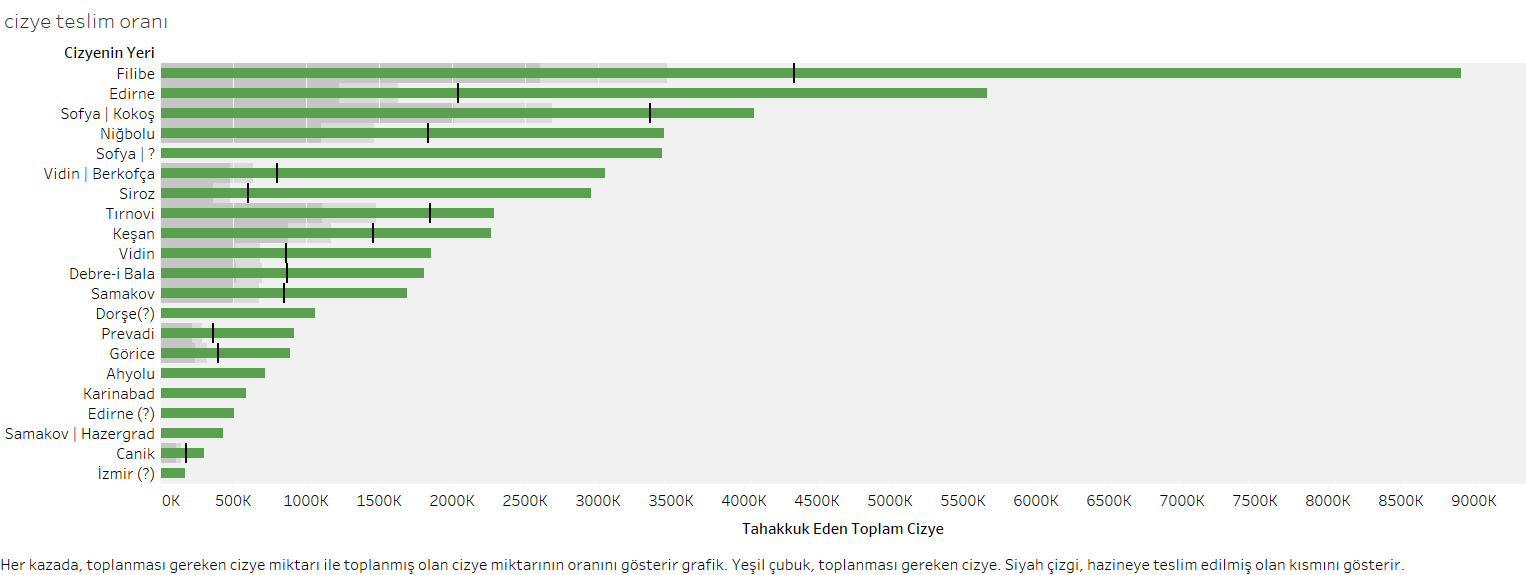

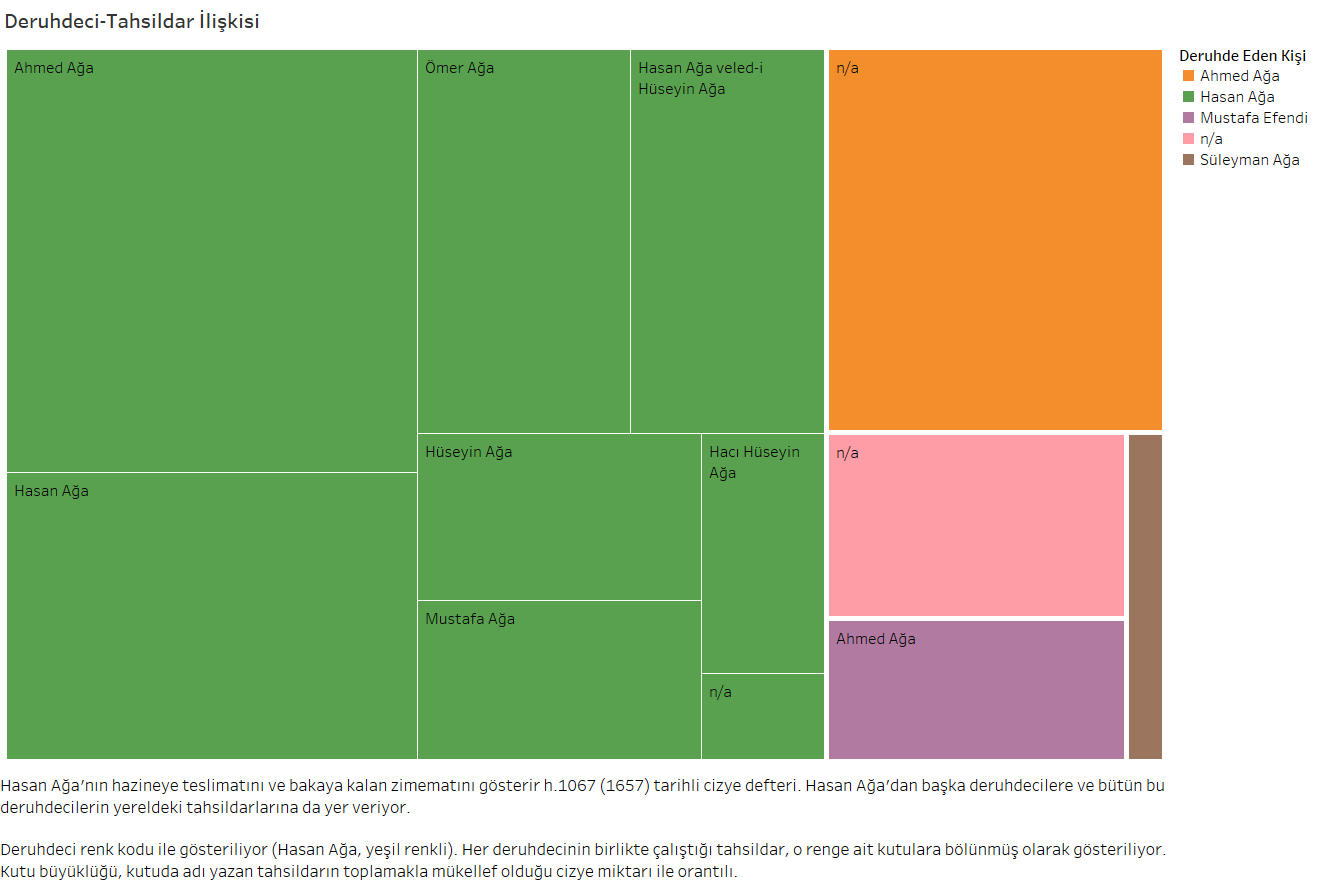

The registry with the archive code BOA MAD.d.3710, which was examined to this end, discloses a part of the provincial network that Hasan Agha established over the jizya (cizye) poll tax distribution and debts. With Tableau Desktop, we visualized the relationships that Hasan Agha and occasionally other contractors established with their collectors in various Balkan settlements.

The archival summary of the aforementioned jizya (cizye) registry is as follows:

"Filibe, Keşan, Prevadi, Siroz, Edirne, Niğbolu, Canik, Samakov, Hezargrad, Dimetoka, Tırnova, Görice, Ahyoli, Karinabad vilayetlerinde daha bazı yerlerin muhtelif senelere ait cizye-i gebranını deruhte eden gümrük emini müteveffa Hasan Ağa’nın müteaddid eşhas marifetiyle yapılan tahsilatından hazineye vaki olan teslimatını ve müteveffa-ı mezbur Hasan Ağa’nın ez gayr-ı teslim bakaya kalan zimematı mikdarını ve daha bazı malumatı ihtiva eden gümrük emini Hasan Ağa’nın zimmeti defteri."

(Customs officer Hasan Agha’s debts registry that includes the delivery that took place to the treasury from the collection that was continuously done specifically by the late customs officer Hasan Agha, who was in charge of the jizya poll tax of Christians (cizye-i gebran) of various years of some places in the provinces of Plovdiv, Keşan, Prevadi, Siroz, Edirne, Niğbolu, Canik, Samakov, Hezargrad, Dimetoka, Tırnova, Görice, Ahyoli and Karinabad. It also contains the amount of debts that remained undelivered by the aforementioned late Hasan Agha.)

Hasan Agha’s religious endowment (waqf) charter (VGM 623)

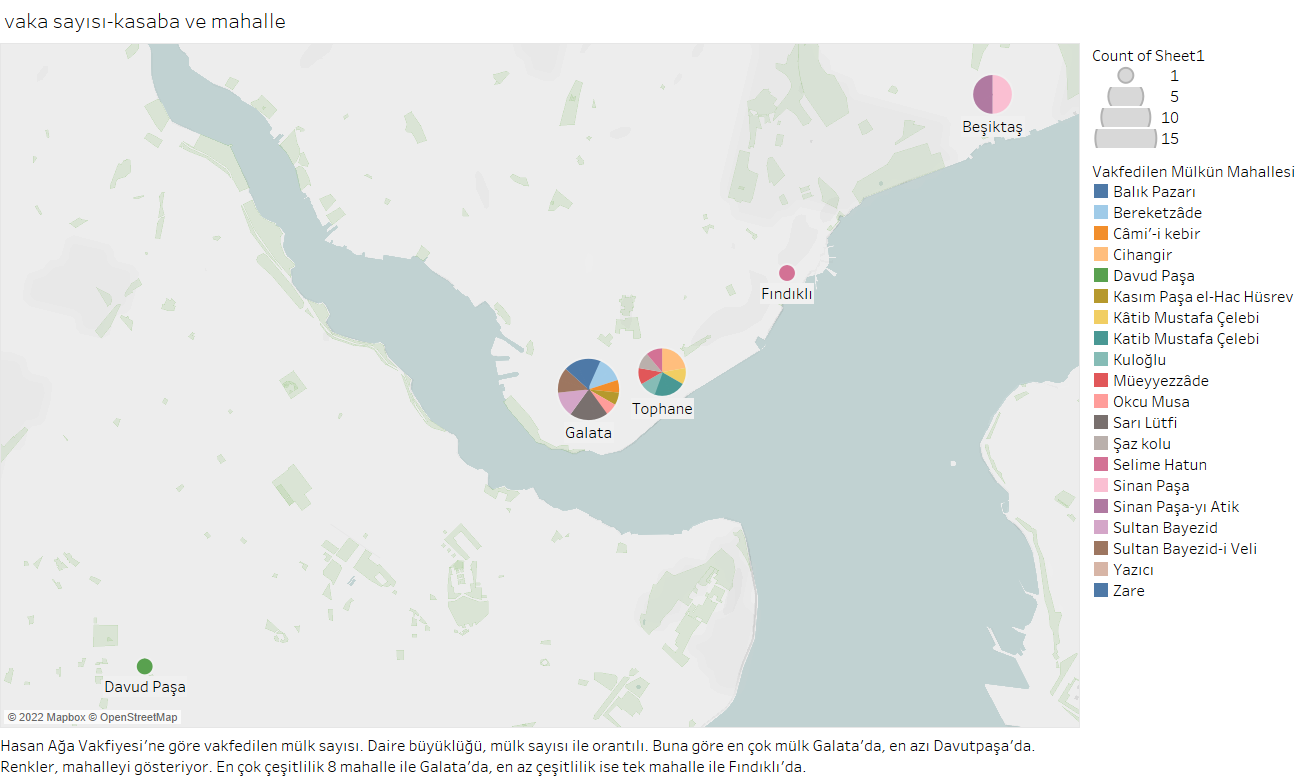

It is known that Customs Officer Hasan Agha established a religious foundation (waqf) and thanks to this foundation gained a respectable place in society. What was the structure of this foundation, the donated goods, and the size of the foundation's income? What was the function of this foundation in expanding and strengthening Hasan Agha's social and cultural ties?

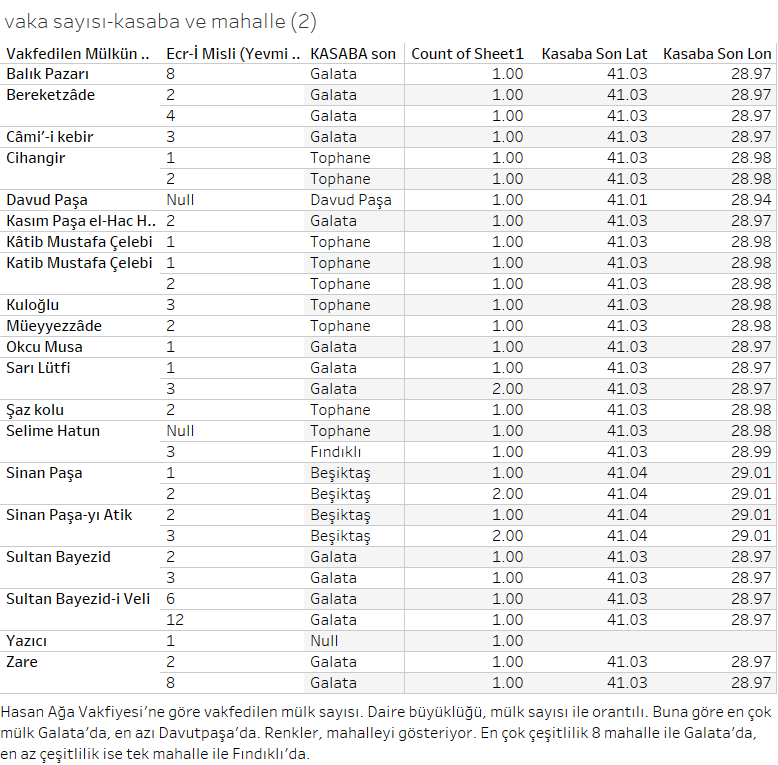

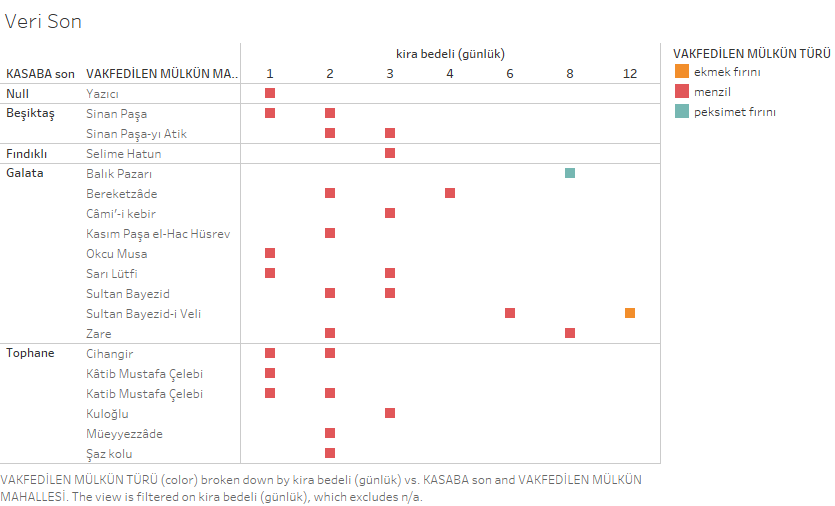

On the map in the link, the distribution of Hasan Agha's rental properties in different districts of Istanbul according to the number of properties can be seen.

Anton Bogos’ Financial and Administrative Power

Muqata'ah of Izmir and Its Surroundings: Incomplete and Inconsistent Data or Early Modern Finances?

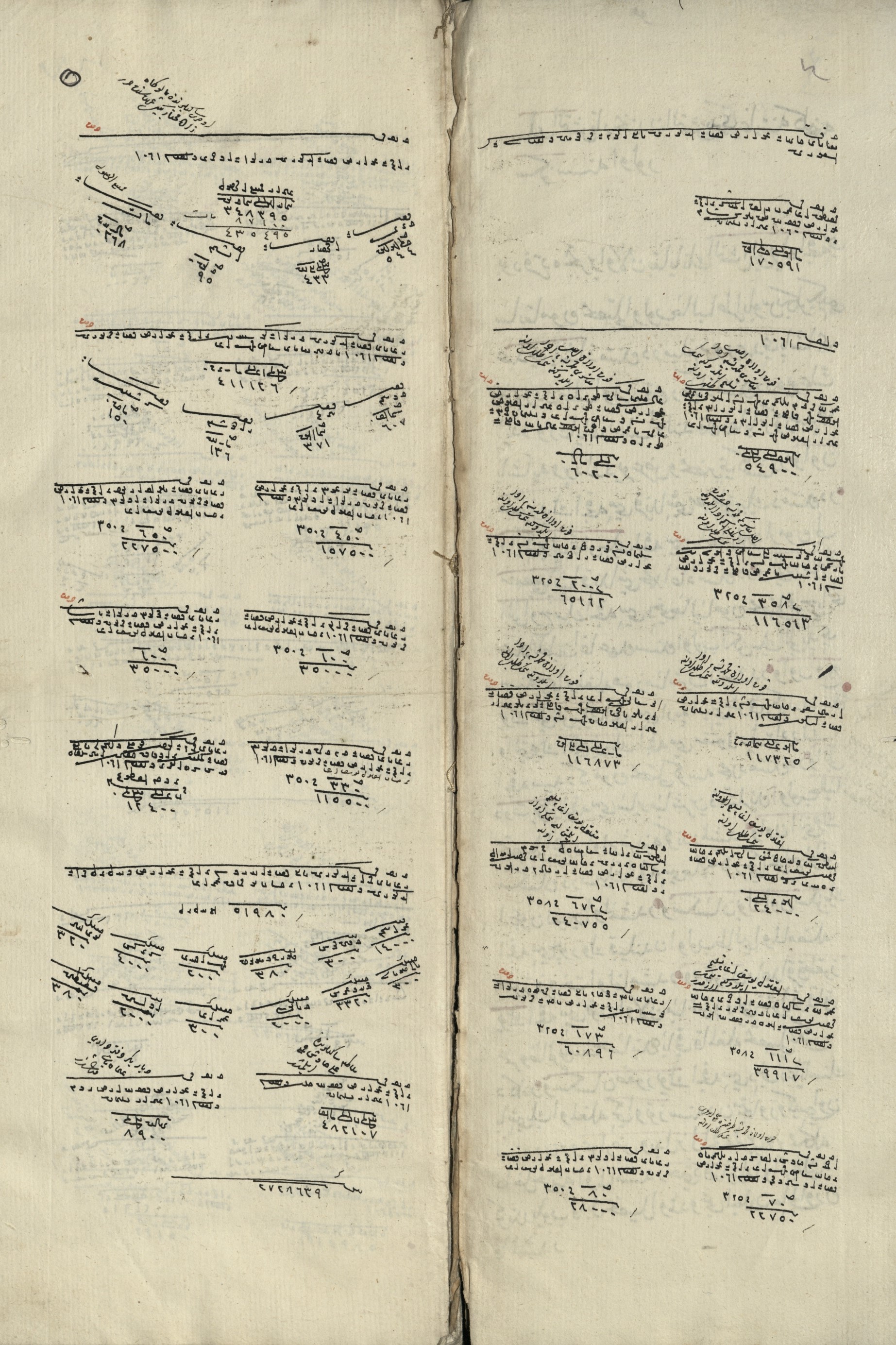

The registry with code D.BŞM.d.182 and dated 1648 (h.1058), during which Anton Bogos was the customs officer in Izmir, shows various revenues (primarily customs) collected from Izmir and its surroundings. Of all the resources examined in this research, this registry was the most difficult to examine using digital humanities methods. Was it because the data was incomplete and inconsistent? Or is it because we have difficulty in examining a source which is sufficiently explanatory within the financial and administrative principles of the early modern period, with the digital analysis methods of the modern period?

In this subsection of the project, we can address these resource challenges as an opportunity to find solutions for the use of digital humanities methods in historical research. For this, we must first take a closer look at the data in the registry. The summary of the registry in the archive catalog is as follows:

Cezire-i Sakız, İzmir, Çeşme, Balat, Urla, Foça-i Cedid, Foça-i Atik İskeleleri Gümrüğü; Aydın, Saruhan, Suğla, Karesi, Midilli, Bozcaada, Erdek, Bandırma, Kapıdağı livalarının beytülmal-i amme ve hassa, kassabiye-i iskeleha, yave-i cizye-i gebran ve kıbtiyan, ispenç, çift bozan, bedel-i avarız-ı ekrad, resm-i kahvelerini, İzmir'deki Yahudilerin döne vergileri, varidat ve teslimatını gösterir defter.

(The registry shows the Customs of the ports of the island of Chios, Izmir, Çeşme, Balat, Urla, New Foça and Old Foça; the public and private state treasury of the provinces of Aydın, Saruhan, Suğla, Karesi, Lesbos, Bozcaada, Erdek, Bandırma and Kapıdağı, the butchery costs of the ports, the Christian and kipczak (gipsy) lost animals and jizya (cizye-i gebran) taxes, bantam, farm breaker’s tax, the cost of the avarız tax of Kurds, and coffeehouses tax, the return taxes, revenues and delivery of the Jews in Izmir.)

From the explanation in the first part of the registry, we learn that this registry concerns the revenues taken upon by Hasan Agha from the beginning of June/July 1647 to the end of April/May 1648. The fact that it was not the name of Anton Bogos, who was the Izmir customs officer of the time, was not mentioned in a registry about the Izmir customs, but rather the name of Hasan Agha, who was the Istanbul customs officer, adds a new dimension to the relations between the two brothers that need to be examined.

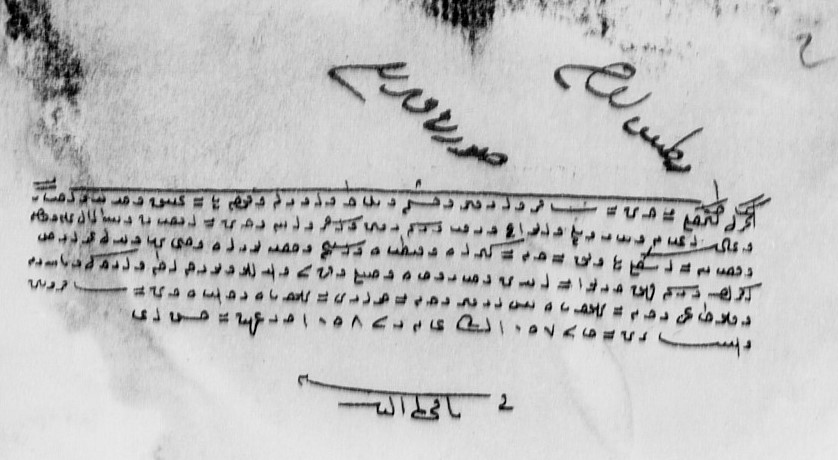

Introductory part of the book numbered D.BŞM.d.182. It is explained that from the beginning of June 1647 until the end of April 1648, it shows various taxes and payments of the towns in and around İzmir, which were under the responsibility of Hasan Ağa.

The registry consists of four sections:

1. Section titled "Teslim-i be-hazine-i amire bi’d-defa’ât" (Multiple times delivery to the Imperial Treasury). 8 deliveries that are planned to (be done to) the treasury within circa one year between March/April 1647 (Safer 1057) and January/February 1648 (Muharrem 1058). These have not yet been delivered to the treasury. Most of these will be collected as salaries of Janissaries, one of these is (in?) akçe, and about the other three there is no explanation about the purpose or source of their collections. The total accrual is 1,089,784 akçe. Half of the collectors were named, the others were not.

2. Section titled "Teslimat" (Delivery). Almost all of the 18 collections (2,418,469 akçe) accrued as a total of 2,463,262 akçe were delivered to the treasury. We know the name of the collector who delivered it to the treasury in 16 out of 18 collections. In 17 cases, we know the local collector in the region. Again, we know the source of this payment collected of these 16. However, it is not specified what it would be spent on.

3. Section titled "Be-hesâb salyânehâ-ı ümerâ-ı Sakız ve Tire" (To the account of salyanes (specific annual tax) of the ümera of Chios and Tire). Almost all of the 14 collections (6,195,911 akçe) accrued as 6,283,879 akçe were delivered to the treasury. In 12 of these, we know the name of the collector. It remains unclear whether the local collector was a different person. In only 3 of the cases, the purpose of the collection (on what it would be spent) was given: the expenses of the castle guards and gunners. However, we do not know the source of the collected income.

4. Section titled "El-vezâif-i mütekâ’idîn ve du’âgûyân ve hüddâm-ı kal’a" (The commissions/duties of the retired, prayer reciters and castle servants). The source of 271,171 akçe collected for the retired, prayer reciters and castle servants is not specified. However, we know to whom how many akçe per day this allocation will be distributed.

Each section of the registry presents information on different topics in different formats. While we see the source of the collection in some sections, we can only see the place where it will be spent in others. While some give the name of the local collector in two stages and the collector who will collect the tax from him and send it to the treasury, some records do not include any names. Therefore, it is not possible to put these sections together in a standardized data table. This situation encourages us to return to the source and ask new questions. Why were these collections consolidated into a single registry? Is Hasan Agha their common feature? Where is Anton Bogos in this network and why is he not mentioned in this registry? How does this registry help us understand early modern Ottoman finance? How similar is it to other accounting records of the period that deal with similar topics? As we examine together the different sources we examined in this research, we will see more closely the network of relationships that can answer these questions.

Introductory part of the registry numbered D.BŞM.d.182. It is explained that it shows various taxes and payments of the towns in and around Izmir, which were under the responsibility of Hasan Agha, from the beginning of the month of Cemaziye'l-avvel of the year 1057 until the end of the month of Rebi'l-Ahir of the year 1058.

Anton Bogos' Estate Inventory Record: Rich But How Rich?

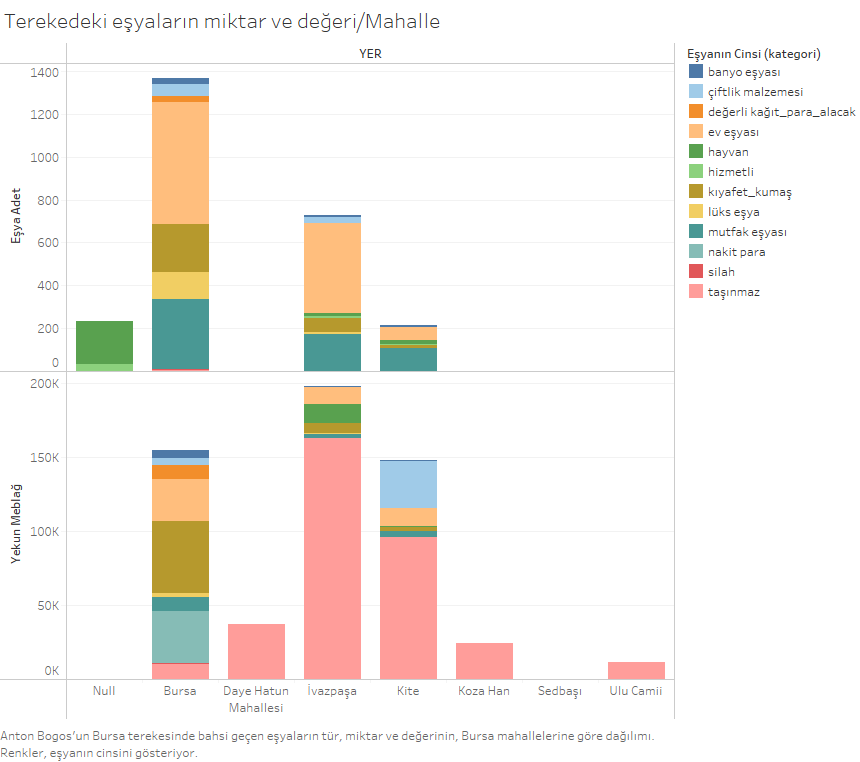

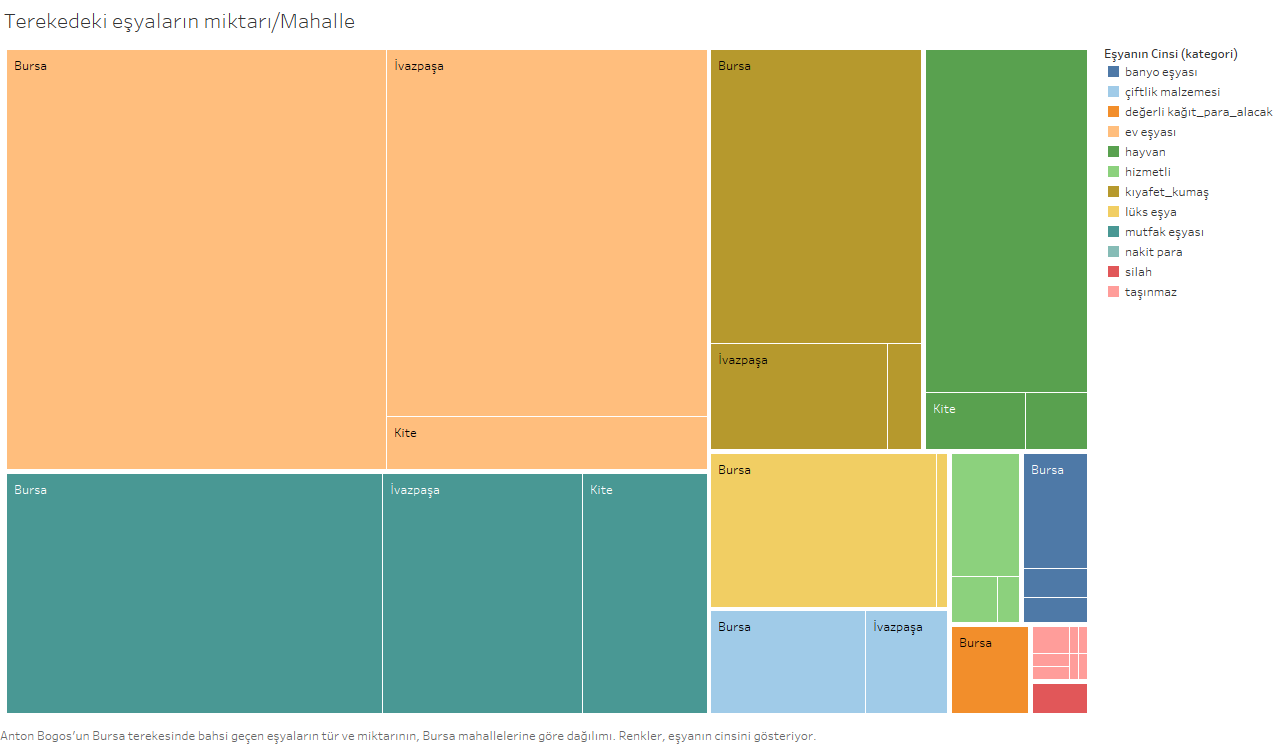

We are conducting a micro-scale sub-study to see where Anton Bogos, who is often mentioned as one of the wealthier people of the period, stands in the 17th-century Mediterranean world in this respect. We are working on the estate inventory record prepared for the confiscation of Anton Bogos’ possessions in and around Bursa, as he had an important position as the customs officer of the silk trade in Bursa, besides his employment as Izmir Customs Officer. We started to analyze this estate inventory record with archive code MŞH.ŞSC 2789 (Bursa B/130) and dated 1656 (h. 1066) in a database after its transcription was finalized. The confiscated property of Anton Bogos in Bursa contains 339 items. In addition to property worth a total of approximately 575,000 akçe, 36 male slaves (gulam) and female slaves (cariye) and 213 cattle were recorded in the registry.

In addition to the assets of Anton Bogos Chelebi, which we have obtained and visualised from the estate inventory records of the mid-17th century in Bursa, the income from the sales of the confiscated real estate, male slaves, female slaves and cattle, and finally the proceeds from the sale of his possessions in Izmir are added. The total amount transferred from Anton's assets to the treasury exceeds 1.4 million akçe. In the middle of the 17th century, the average wealth in Bursa was around 142,000 akçe. In the estate inventory records of the same years, there are only two estates worth 600,000 akçe. When we look at the whole of the 17th century, the number of people with a wealth of more than 1 million akçe in the nearly two thousand estate inventory records in the court registers of this city is only 21. (We thank Chris Whitehead and Hülya Canbakal for sharing the information in this paragraph with us.)

The Research Team

Principal Investigator

Senior Researchers

Project Consultant

Research Assistants

Mert Pekdoğdu

Boğaziçi University